LAGOS — Adegunji Kazeem vividly remembers the day his life fell apart.

It was December 4, 2019. Kazeem was a final-year student at the University of Lagos and writing his undergraduate thesis, a requirement for graduation.

All five chapters of the thesis were on his laptop, an HP Envy running on Windows 7 that he had spent several months saving up for with a day job as a teacher. Kazeem switched it on. Suddenly, a malware infection scrambled his laptop, making his thesis inaccessible.

Kazeem’s computer had not been compromised by an expert hacking technique. It was an easy target because his Windows 7 operating software was pirated.

After paying ~100k naira (~$250, based on exchange rates at the time) for the laptop, which was used, it would’ve cost another ~50k naira to cleanse the system and install legitimate software. The only thing he could afford was a deal offered by the PC technician who sold him the computer: 2k naira (~$4.50) for counterfeit Windows 7 and the Microsoft suite.

In the United States and Western Europe, software — from Windows to Adobe to Microsoft Office — is easy to purchase and relatively affordable for the middle class. But it’s a much different story in the developing world.

In Nigeria and many other countries in Africa, Asia, and South America, average residents have fewer options for accessing legitimate software. Underground economies abound where vendors burn pirated software from the dark web onto DVD discs and sell it at marketplaces alongside the real stuff.

The result is that the vast majority of software installed on devices in these countries is unlicensed, with many purchasers unable to afford legitimate software or not realizing the difference between counterfeit and real. The large market of illicit software drives a lack of security, which leaves people like Kazeem — and numerous small businesses — vulnerable to malware infections.

Counterfeit software for sale near Lagos. (Olatunji Olaigbe)

In addition to his thesis, the malware prevented Kazeem from accessing family pictures and Excel sheets he needed for his job as a teacher.

“Eighty percent of my digital existence was lost that day,” Kazeem recalled.

The software divide

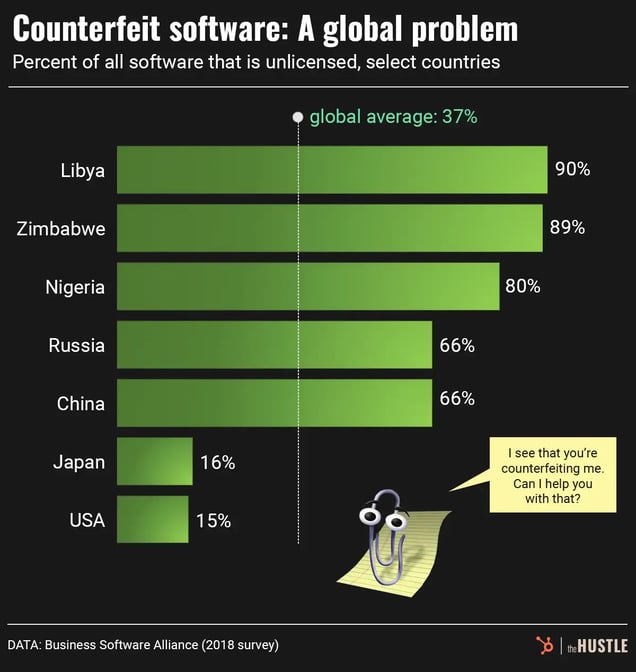

According to a 2018 report by the Business Software Alliance (BSA), 80% of all software packages in Nigeria are unlicensed. That puts Nigeria among the countries with the largest counterfeit-software problems, but it’s hardly an outlier.

- Worldwide, ~37% of installed software is unlicensed, according to the BSA, comprising a market of $46B. (Terms like “unlicensed,” “counterfeit,” and “pirated” are often used interchangeably to describe the production and sale of illicit software.)

- In the US, ~15% of software is unlicensed. But it is an exception. In most countries, there is more counterfeit software than authentic software.

African countries are earmarked with a high rate of unlicensed software. The country with the highest rate, Libya, was tagged at 90%, followed by Zimbabwe at 89%. The only African country that had less than 50% was South Africa, at 32%.

The Hustle

A spokesperson for the BSA, which includes software companies like Adobe and Microsoft as members, told The Hustle that unlicensed software is linked to security issues like those experienced by Kazeem and can lead to other societal costs, including the loss of taxable revenue.

The damages wrought by counterfeit software often cost more than the price of licensed software. The BSA estimates the global cost of malware infections from counterfeit and unlicensed software to be $359B annually, and that it costs up to $10k to fix a single computer.

But in developing countries it’s hard for many individuals and small businesses to pay those upfront costs:

- Nigeria’s annual per-capita GDP was ~$2k in 2021, and nearly two-thirds of the population lives in extreme poverty.

- More than 50% of Nigeria’s 200m residents do not have basic digital literacy.

Nigerian users of pirated software told The Hustle that licensed software packages were simply too expensive and the counterfeit packages were too hard to pass up.

One music producer we talked to said he could buy a licensed edition of Adobe Audition for 15k naira (~$32) in Nigeria. A counterfeit version of the entire Adobe 2022 suite costs just 2k naira, or ~$4.50.

Welcome to Computer Village

The music producer discovered the cheap, counterfeit version of Adobe at the country’s famous electronics hub: Computer Village.

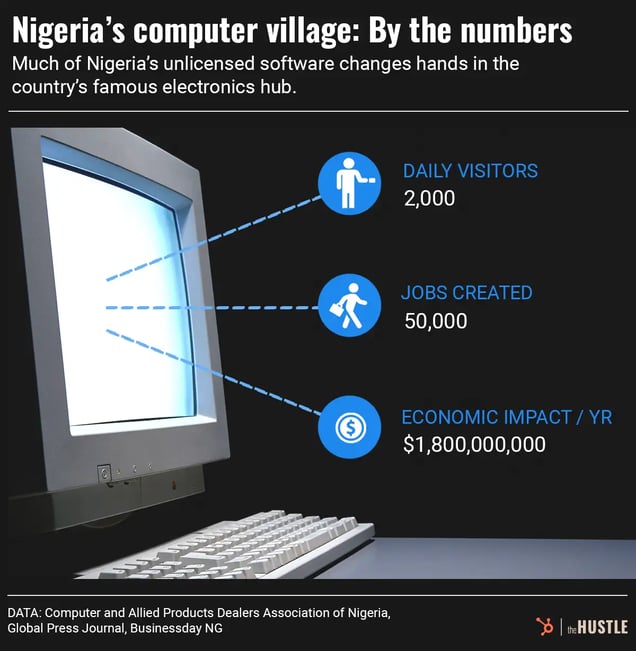

Located in Ikeja, the capital city of Lagos State, Computer Village was once a typical residential area. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, locals began transforming homes and apartments into stores selling computers, phones, and other electronics, turning it into what is considered the IT capital of the country.

Shoppers and vendors mingle at Computer Village. (Getty Images/Anadolu Agency)

Now, Computer Village is home to over ~5k vendors across seven busy streets, selling, buying, and swapping tech items every Monday through Saturday — often with little to no care about where their goods come from.

On a recent Thursday, the market was bustling. Vendors stood under kiosks, sat in roadside shops, and looked down from the top floor of multi-story plazas, all trying to cut a deal. Middlemen scurried across the streets, trying to cash in on whoever looked like they did not belong.

In the throng of activity, it was difficult to find where to buy licensed software. But the vendors selling unlicensed software were easy to spot.

The Hustle

They parked wheelbarrows strategically at the junction where the main roads turn to alleys. The wheelbarrows were stocked with DVD discs in neatly wrapped paper covered with pixelated logos of the software package being sold.

- Unlicensed software packages ranged from Microsoft Office 2022 to AutoCAD and SPSS to gaming and media production software. There was even software used to produce other software packages.

Many vendors and middlemen at Computer Village and other markets around Lagos don’t realize they’re selling counterfeit software. Others know exactly what they’re selling.

How counterfeit software proliferates

John, a vendor who requested to use a pseudonym for fear of repercussions, had a wheelbarrow full of counterfeit software at Computer Village. His cheapest software went for 500 naira, but he’s sold it for as much as 5k naira — a special request preordered by a customer.

He said he moved to Lagos from a rural town in southeast Nigeria in 2010, working as a shop attendant in a car-parts store. The money wasn’t great, and a friend introduced him to piracy, just as the market for pirated movies and TV shows was picking up.

- The Nigerian economy, the largest in Africa, has sputtered for over a decade. According to the World Bank, the unemployment rate is ~33%.

- Trading is a lifeline for many young Nigerians, and Computer Village alone has created ~50k jobs, many of which involve the sale of legitimate computers, phones, software, and electronics.

After first pirating movies and TV shows, John said he was arrested a couple of times and decided to switch to a different trade: selling unlicensed software.

John has a flash drive that he says contains 90% of all the software he sells. From that drive, he burns the software on discs. After packaging the burned disc in plastic paper printed from a color laser printer, he’s ready to sell.

On good days, John makes ~10k-20k naira (~$20-$45), giving him a better salary than minimum-wage jobs in Nigeria, which pay 30k naira per month. And it’s a high-profit-margin business: His main expense is the constant supply of empty DVD discs, which cost no more than 100 naira each.

Occasional raids have occurred at Computer Village, but, according to John, software piracy is safer than pirating movies, and arrests have declined since the late 2010s.

Another software counterfeiter we talked to agreed that arrests had gone down, saying efforts to tackle software counterfeiting had shifted from punishment of counterfeiters to improving accessibility and awareness regarding legitimate software.

To deter usage of unlicensed software, the BSA says it has focused on educating people and businesses and on engaging with countries to develop more practical regulations and laws.

Counterfeit software rates went down by five percentage points worldwide between 2012 and 2017, according to the BSA’s 2018 report, but only down by two percentage points in Nigeria.

Experts have questioned whether the counterfeiting problem can be eradicated without massive companies like Microsoft changing their sales models.

- According to researchers at University of Bechar, Algeria, these companies’ proprietary softwares lead to high prices, creating a barrier for people in developing countries and furthering a digital divide. While the researchers say software pirates “divert the labor of others,” they argue that “multinationals block the propagation of knowledge.”

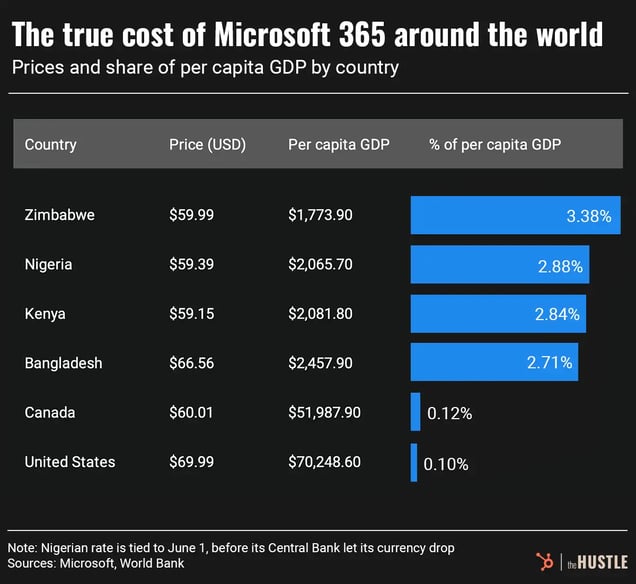

- They recommended indexing software prices based on a country’s average income. Despite Nigeria’s per-capita GDP being more than 90% less than the per-capita GDP of the US, a yearly subscription to Microsoft 365 in Nigeria is only ~14% less expensive. (Microsoft representatives declined an interview request from The Hustle.)

The Hustle

For now, average Nigerian businesses and people like Kazeem will continue to face difficult choices, remaining in the dark about counterfeit software or knowingly purchasing it and hoping for the best.

After Kazeem’s ordeal, he recovered bits and pieces of his thesis but had to redo much of what he had already written. He also found a new PC technician for his next software purchase. The technician sold him pirated versions of Windows 10 and Adobe but explained the risks, and he offered to connect him with others to share a Microsoft 365 family plan.

He also installed an authentic version of Kaspersky antivirus software on Kazeem’s computer to ward off malware, giving Kazeem greater hope that he won’t face the same problems as last time.

“My antivirus,” Kazeem said, “is legit.”