On one end of the spectrum, there is Elon Musk. On the other end, there is Iceland.

Musk, like many celebrity CEOs, works a lot of hours. He once bragged about spending 120 hours a week in the factory to supercharge Tesla’s production. After that made him “bonkers,” he toned it down to around 80 hours.

Iceland recently shared the results of its workforce switching from 40-hour workweeks to 35 or 36 hours, finding the workers were just as productive.

What if both are getting it wrong?

Whether it’s the grueling approach of Musk or the leaner approach of Iceland, hours and structure are how we typically measure work, even though the relationship of time to success makes little sense.

“Everybody is aware that time is a poor substitute, but we’ve taken up the assumption that our output is proportional to hours,” John Pencavel, a Stanford economist, told The Hustle.

The pandemic has accelerated conversations about remote work, hybrid scheduling, and 4-day workweeks (an idea that has been trotted out since at least the 1970s and never stuck). But some scholars propose a more radical alternative to time-based work: destroying the clock altogether and just getting stuff done.

That means working when we’re at our best, and around our family and health priorities, instead of from 9 to 5, or 8 to 6, or longer to try to impress our boss.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Obviously, not every job can be measured by task: Cashiers at stores, servers in restaurants, and nurses working night shifts, for instance, will always have to hew to some type of timed schedule to accommodate customers or patients.

Nor are we suggesting America is ready for an economy in which Amazon employees — already tasked with strenuous labor — are paid solely by the number of shelves they stock in lieu of a guaranteed wage or salary.

For this article, we’re focusing on jobs in the information economy, where the setting and hours of many people’s jobs have been in flux for the last 20 months.

When someone asks us how many hours we work every week, we should all have the same answer: I don’t know.

Why time is bad for many professions

When the 40-hour week was standardized in 1938 through the New Deal’s Fair Labor Standards Act, it was a huge victory for reformers and labor unions. They had fought for years to ensure better wages and realistic schedules for workers.

Much of the work done by Americans in the first half of the 20th century, particularly in the automobile industry, was based around the assembly line. One person’s output was largely dependent on another’s. Time was the most sensible option for measuring work.

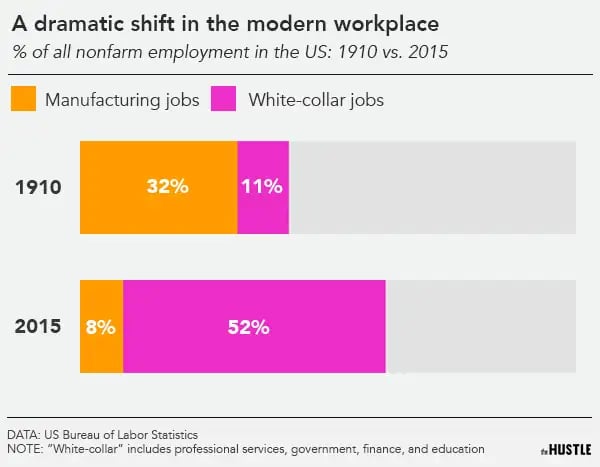

In the last half of the 20th century, the economy saw dramatic shifts. Between 1910 and 2015:

- Manufacturing jobs declined from 32% to 8% of all nonfarm employment.

- White-collar jobs (professional services, government, finance, and education) increased from 11% to 53%.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

“Fundamentally, for much of the work that we do today, time is irrelevant,” Tammy Erickson, a consultant and longtime evangelist of task-based work, told The Hustle. “It doesn’t really matter.”

“For example, if I’m a client for an accountant, I want to have my annual report done well, however many hours it took your team to do that,” she said. “I don’t care if it took them a zillion hours or 10 hours. I want a good annual report.”

Yet the focus on time has stayed the same, particularly on conflating longer hours with better performance.

From 1979 through 2004, college-educated men in white-collar jobs drove an increase in the share of employees working 50 or more hours per week after nearly continuous declines for the previous century, and they were given more opportunities and higher salaries.

Using results over time has worked

To think about why time doesn’t matter, look no further than someone like Kevin Durant.

He and other star athletes are evaluated based on performance, on points and assists and other metrics, not on how many hours they spend honing their craft in the gym or how long their games last.

But there’s also a famous example in a traditional white-collar setting: Best Buy.

Best Buy presents a promising case study in measuring work by results instead of by time (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

When Jody Thompson started working in Best Buy’s HR department, she says employees felt pressure to stay at the office after 6pm regardless of whether they needed to get something done. Sometimes when she left for the day she’d leave her coat behind so it looked like she was in another part of the building.

In the mid-2000s, she and fellow HR employee Cali Ressler led a movement known as the Results Only Work Environment (ROWE) to help the electronics giant attract more talent. Employees were told to forget about time and place and just finish their assignments.

The goal wasn’t flex scheduling or remote work, as those designations suggest employees would merely request changes to a standard 9-to-5 style workday. It was for employees to have complete control over their schedule, no questions asked.

ROWE rests on 2 key concepts: autonomy and accountability.

“Autonomy means I’m self-directed and independent. So each day, because I know what I’m accountable for, I choose the best time and the best place to do my work in concert with others. I choose it,” Thompson told The Hustle.

The results for Best Buy were mostly positive.

- Productivity increased by 41%, and employee turnover was drastically reduced.

- Better yet, a study by the University of Minnesota’s Phyllis Moen showed Best Buy workers slept more, were less likely to come to work sick, and experienced a reduction in work-family conflicts.

Many employees didn’t work less — some reported working more — but they felt in control. They skipped out of the office for the occasional afternoon matinee, took conference calls while hunting, and picked up their kids from school.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

But the Results Only Work Environment took root just ahead of the Great Recession and as Best Buy struggled with the leap to ecommerce.

In 2013, new CEO Hubert Joly canceled ROWE, describing it as “fundamentally flawed from a leadership standpoint.” A spokesperson for Best Buy said workers needed to be “all hands on deck,” which meant “having employees in the office as much as possible.”

Sound familiar?

Well-known CEOs like Apple’s Tim Cook and JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon have expressed the same sentiment about post-pandemic work plans. Other companies, like Google, have announced hybrid work policies requiring scheduled office time a few days per week.

This is the hard part about results-based work:

- It comes unnaturally to executives and managers, given their contributions (how much does delegation and leadership really count for?) are difficult to gauge.

- They also have the most to learn and the most to give up as they grant greater autonomy to employees.

So how do we make results-only work happen?

There is no magic bullet for reversing decades of reliance on the clock. But there are some encouraging signs.

While the back-to-the-office mandates from JPMorgan and Google indicate a reluctance to change, Thompson has heard from plenty of other companies that want her help building a ROWE culture.

She also sees it happening in the country’s record resignation rate. People are leaving their jobs because they are tired of long hours and rigid schedules. Companies may eventually feel so much pain from the attrition that they change their ways.

Bringing back freedom to our lives

The best reason to rethink time and work isn’t about economics (although cases at Best Buy and elsewhere show focusing on results is better for business). It’s about embracing a healthier culture for everyone.

Joan Williams, director of the Center for WorkLife Law at UC-Hastings, has used the term “ideal worker” to describe the types of management-approved employees who have flourished in workplaces that reward putting in the time.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

The ideal worker is someone who has 100% commitment to work and displays “their strength and stamina and commitment by working wild hours,” Williams told The Hustle.

Usually, only men can fit the ideal worker mold, as women shoulder a disproportionate share of caregiving and home responsibilities. And the ideal worker is, needless to say, somebody who has little freedom over their life.

That’s really what time-based work schedules have been taking away from us: our freedom.

By losing the structure of time and focusing on the results, we can get freedom back. Freedom to take care of children or elderly parents. Freedom to exercise. Freedom to start a new hobby. Even the freedom to do our best work.

Let’s break our addiction to the clock and see where we can go.