On September 13, 1984, as stocks wavered through a bear market, a regional electronics chain held a hyped initial public offering.

If it seems odd that a purveyor of VCRs and stereos could make investors swoon, remember that this was the 1980s, and people were getting pumped about cellular phones that were roughly the size of microwaves. And know that this electronics company was Crazy Eddie, a brand that, in so many ways, was breaking the usual rules.

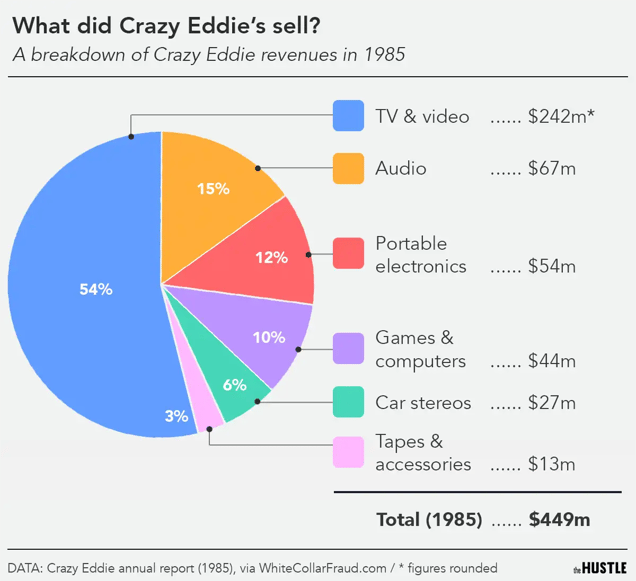

The previous fiscal year, Crazy Eddie’s annual revenues were ~$134m, or ~$372m today. More impressively, the 13-store New York City-area chain led the electronics industry in sales per square foot and profit margins.

Crazy Eddie was also a cultural sensation, rising to fame with absurd commercials that Dan Akroyd parodied on Saturday Night Live. In the 1984 movie Splash, Darryl Hannah’s character watched a Crazy Eddie ad when she first discovered TV.

That first day, investors purchased nearly 2m shares of Crazy Eddie for $8 apiece, under the ticker CRZY. By the end of the year, the stock would climb 25%, far outpacing a flat market and boosting Crazy Eddie’s plans for greater expansion.

There was just one major problem.

Crazy Eddie had been lying about its numbers since its inception — and the higher the stock soared the further founder Eddie Antar went to maintain the illusion.

“It was Goodfellas,” one attorney later told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “except they operated with briefcases instead of guns.”

The insaaaaane rise of Crazy Eddie

Eddie Antar was a 22-year-old high school dropout when he opened his first store in 1969, near the Sheepshead Bay neighborhood of Brooklyn.

He was the classic outer-borough tough guy: almost bald with a scraggly goatee, allergic to wearing anything but sweats, crude yet charming at the same time.

Eddie Antar (AP, via New York Times; 1993)

Antar believed people would flock to stores that sold items like speakers, VCRs, and televisions under the same roof — and he was right.

Industry-wide, sales of electronics jumped from $8.5B in the late 1960s to $35B by the mid-1980s.

By 1979, Antar had 8 stores and shared the success with his family, which was part of a tightknit Syrian Jewish community in Brooklyn. His father, Sam M. Antar, uncle Eddy Antar, and brothers Mitchell and Allen Antar all held key positions.

Meanwhile, Eddie Antar made sure everyone in New York City knew his business by flooding TV and radio with catchy ads shaped by advertising director Larry Weiss.

Weiss was well-connected in the radio and music industries and hired radio DJ Jerry Carroll to be Crazy Eddie’s spokesperson. (Other candidates for the job included the Godfather of Soul, James Brown.)

Taking inspiration from the humor of Mad magazine, Weiss developed commercials that played off music trends and the cultural zeitgeist. Most commercials featured Carroll delivering the signature catchphrase, “His prices are insaaaaaaaane.”

A montage of scenes from an off-beat Crazy Eddie TV spot, featuring the DJ Jerry Carroll (YouTube)

The ads were as catchy as they were unavoidable. By the early 80s, Crazy Eddie was spending ~$5.5m (~~$15.3m today) on advertising and claimed to be the largest purchaser of radio and TV advertising in the New York market.

And Antar built upon the ubiquitous marketing with innovative customer service:

- Crazy Eddie stores stayed open on holidays and Sundays, at a time when many retailers still followed a Chick-Fil-A schedule.

- Antar rarely listed prices in ads but guaranteed he would have the lowest prices in New York and matched competitors’ offers if his customers found a better deal. Fewer than 1 in 5 Crazy Eddie customers tried to match prices.

“In business — and in life in general — he was daring and took chances, and wasn’t afraid of consequences,” Weiss told The Hustle.

Weiss had no idea Antar was partaking in business practices that were more daring than he could imagine.

‘Nothing should go to the government’

Every night starting at 10:30, Crazy Eddie store managers descended on the Brooklyn home of Antar’s uncle (also named Eddy). They came with bags full of cash, checks, and receipts.

Antar’s uncle used the cash to pay off expenses and then put the rest in a briefcase. When the briefcase got too full, he stored the cash under a radiator. And when there was no more room under the radiator, he started bringing the money to Antar’s father’s house, where he hid as much as $3.5m — ~$11m today — in a false ceiling.

Eddie Antar kept close tabs, usually calling his uncle twice a day to see how much money they were skimming. A family member later said Eddie Antar received ⅔ of the skimmed cash and Sam M. Antar, his father, the other third.

The skimming strategy allowed Antar to not only hoard cash but also evade sales taxes. His employees were also paid off the books so Crazy Eddie could avoid payroll taxes.

“There was a culture at Crazy Eddie that said nothing should go to the government,” wrote Antar’s cousin Sam E. Antar, who eventually became CFO at Crazy Eddie and has detailed his work in a series of blog posts.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

As Antar’s business empire expanded, he vacationed in Europe and South America and bought properties at the Jersey Shore and in Miami. He churned through cars like they were clothes, once abandoning a vehicle on the Garden State Parkway and leaving it to burn.

He also kept as much as $200k in cash stashed under his bed at any given time.

“Money was always in the house,” said Debbie Rosen Antar, Antar’s first wife, to investigators in the late 1980s. “And if I needed it and I asked him, he would say, ‘Go underneath the bed and take what you need.’”

Despite the success, Antar managed to keep a low profile, content with letting people think Jerry Carroll was Crazy Eddie and declining almost all interviews. If his workers talked to the press, it was usually on the condition of anonymity because they didn’t want to say something stupid and end up on the wrong side of their boss.

They knew the key to staying on Antar’s good side. As one employee told the New York Daily News in 1984, “He respects loyalty.”

A rising stock and an angry family

Why would a company built on a family fraud go public?

Somebody told Antar he could keep making millions skimming cash, but he could make tens of millions if the company traded on the stock market.

Strangely, Crazy Eddie’s fraudulent history gave it an advantage. To provide the illusion of quickly increasing profits ahead of the IPO, the Antars simply reduced the amount of cash they were skimming. With millions more on the ledger instead of in the family’s pockets, the company’s profits looked more impressive.

As a public company, Crazy Eddie then made up for its inability to skim cash by initiating new fraud streams.

- The company embellished its inventories by millions of dollars to appear better-stocked and better positioned for profits.

- The Antar family laundered profits it had previously skimmed — and deposited in foreign bank accounts — back into the company to inflate revenues.

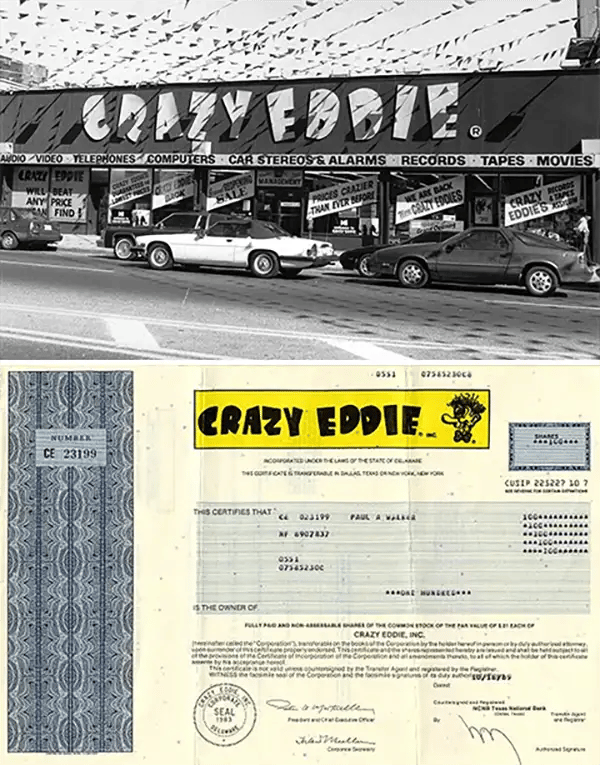

TOP: A Crazy Eddie store in the ‘80s (Anthony Pescatore/NY Daily News Archive / Getty); BOTTOM: A Crazy Eddie stock certificate (Scripophily.net)

Outside the family, nobody had a clue something fishy was going on, least of all Crazy Eddie’s auditors.

To conceal the fraud, employees shuffled excess merchandise from store to store or borrowed it from friendly competitors to make inventories appear larger. As an added protection, Sam E. Antar says he distracted the auditors, who were mostly single men, by setting them up on dinner dates with Crazy Eddie’s most attractive workers.

From 1984 to 1987, Crazy Eddie grew to 43 stores and its stock price reached $79. Antar and other family members sold most of their stock at elevated levels, cashing in a purported ~$90m and fooling investors.

“We arrogantly committed our crimes simply because we could and we had no empathy whatsoever for our victims,” Sam E. Antar later wrote.

But some family members were not pleased with their take.

Despite enriching their pockets with stock and above-market salaries, tensions had flared for years, with Eddie Antar’s father and 2 brothers jealous of his status as family patriarch.

The turning point was on New Year’s Eve in 1983, a few months before the IPO. Antar’s father tipped off his daughter and Antar’s wife that Antar would be on a date with his mistress in Manhattan. They caught him in the act, and a street fight nearly erupted.

Family problems led to business problems for Eddie Antar (Courtesy of the Courtroom Sketches of Ida Libby Dengrove, University of Virginia Law Library)

Antar’s father later described the blowup as the “New Year’s Eve Massacre.” It created a simmering family feud that boiled over when the business went south.

In 1987, Crazy Eddie started losing money as the electronics industry grew more competitive and it struggled to manage its many new stores. The stock sank like a rock, to below its IPO value. In November 1987, a hostile investment group led by Houston entrepreneur Elias Zinn pounced, purchasing Crazy Eddie.

As Antar’s cousin later recounted, Antar thought the sale would at least give them an opportunity to pin the fraud on the new owners. But Zinn immediately discovered $45m of listed inventory was missing. Stores soon closed, and the company went bankrupt in 1989.

Worse for Antar was that 2 disgruntled ex-employees teamed up with Antar’s father to lodge a fraud complaint with the SEC. The FBI started sniffing around, too.

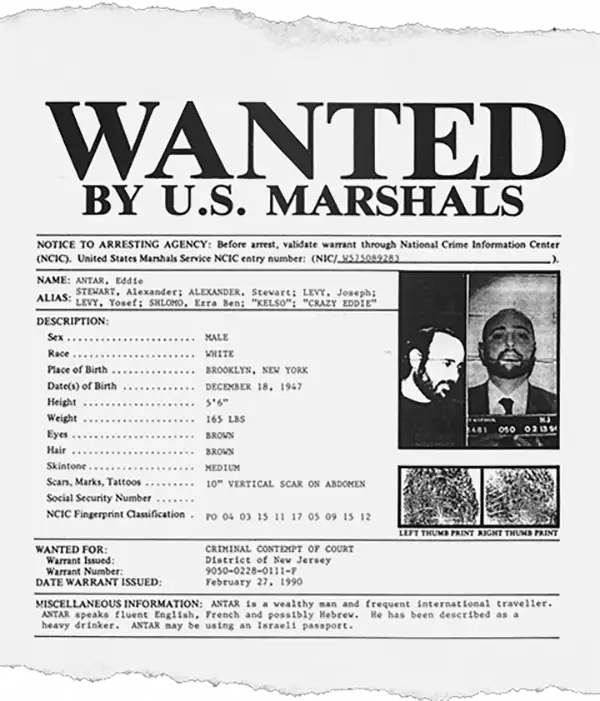

In February 1990, Antar fled the country.

Over the next 2 years, he used forged Brazilian and Israeli passports to globe-trot through Tel Aviv, Zurich, São Paulo, and the Cayman Islands, with an estimated $60m at his disposal.

The ‘Darth Vader of capitalism’

On June 24, 1992, Israeli police stationed themselves outside a luxurious home in a suburb of Tel Aviv. Authorities, including the US Marshals and Interpol, had grown suspicious after detecting a money transfer between 2 names believed to be aliases for Antar.

The police arrested Antar and raided the home, uncovering $60k in cash, passports, birth certificates, and paperwork for forming a corporation without a lawyer.

Antar was on the run for ~2 years before getting caught in Israel. (Wikimedia Commons)

Antar faced a federal trial a year later for bilking investors out of hundreds of millions of dollars in multiple stock and bond sales.

The US Attorney’s Office for the District of New Jersey, headed by future George W. Bush cabinet member Michael Chertoff, revealed details that seemed to be plucked from a Scorsese film. Antar had…

- Assumed names like David Boris Levy and Harry P. Shalom

- Created Liberian shell companies

- Strapped $100k to his chest before boarding a plane

The press compared the Antars to the “Addams Family” and to the Ewing family from the TV show Dallas.

Still, the case was hardly a slam dunk. There was basically no paper trail, and inventory fraud isn’t the easiest concept to grasp. Antar might have escaped a conviction if he hadn’t eschewed what he expected out of his own employees: loyalty.

Before fleeing the US, Antar had abandoned Sam E. Antar, who was facing enormous pressure from the feds because he had orchestrated much of the fraud as leader of Crazy Eddie’s finances. Sam E. Antar ended up pleading guilty to 2 offenses in exchange for testifying and was the prosecution’s star witness in a trial that stretched on for weeks.

At sentencing, the US Attorney’s Office asked for — and received — the maximum allowable sentence of 12.5 years. Antar was ordered to repay $121m to investors.

“He is a kind of Darth Vader of capitalism,” Chertoff said at the sentencing hearing.

But his fraud didn’t involve any special mastery of the laws. Anyone could have done it.

“It was completely brazen,” Paul Weissman, who also prosecuted Antar for the US Attorney’s Office for the District of New Jersey, told The Hustle. “It was about as basic as you can get.”

Eddie Antar is led by an Israeli police detective for a remand hearing in 1992 (SVEN NACKSTRAND/AFP via Getty Images; edited by The Hustle)

Antar was released from prison in 1999.

After his release, he apologized to and reconnected with Larry Weiss, his former marketing director, and they launched CrazyEddie.com. In an entirely different world for consumer electronics, there was no comeback for Antar. The business venture failed.

Out of prison and no longer in the limelight, he agreed to interviews every so often before his 2016 death. Antar, who deflected blame for his crimes onto his family, thought of himself as more of a trendsetter than a fraudster.

“Everybody knows Crazy Eddie. What can I tell you?” he told The Record in 2012. “I changed the business. I changed the whole business.”