Sy Montgomery spends money on three things: gas, groceries, and making the New York Times bestsellers list.

For years, she and her husband have lived as freelance writers deep in the mountains of New Hampshire. They’ve eked out a living, she says, because they’re so frugal that even at 65 years old she wears hand-me-down clothes from friends.

“We can live off the smell of an oily rag,” she says.

When Montgomery learned that her publisher wasn’t going to give her third book, The Soul of an Octopus, the national book tour that her first book, an international bestseller, had received, she took matters into her own hands.

She hired a PR pro and self-funded a tour in 2015, charming audiences in bookshops across the country with tales of how animals can expand our consciousness.

“I’m just lucky my husband let me gamble with our savings that way.”

Her bet worked — The Soul of an Octopus hit the New York Times bestseller list the month of its release.

Montgomery had learned an important lesson. Bestsellers don’t just happen; they’re made, by a murky engine of influence that includes the very list itself.

The list effect

The New York Times bestseller lists, of which there are weekly, monthly, and genre-specific varieties, have long been arbiters of culture, shadowy mixes of dictum and data. “It’s a bully pulpit,” Montgomery says. Which is to say, it offers a platform, but not a golden ticket.

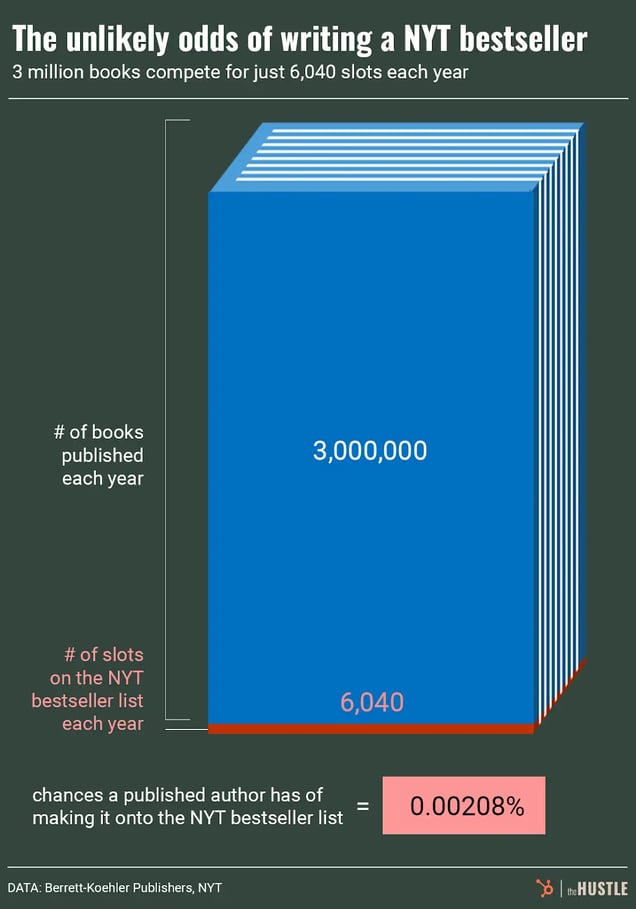

Making the list is a herculean task. Consider the number of books, more than 3m, published every year. And then consider that the number of slots on the NYT’s coveted lists is ~6240. That gives authors a coolly aspirational 0.00208% chance to snag one.

The Hustle

Numbers aside, the recipe for its creation has long been a trade secret.

Behind the list is another list, one curated to include books projected by publishers, booksellers, and editors to be bestsellers, according to Laura B. McGrath, assistant professor of English at Temple University. How to make it onto that list is a mystery.

“The New York Times only tracks the data for those pre-selected books, not for all books that get published. So the curatorial process is itself pretty dramatic,” McGrath says.

Laura McGrath teaches a course on the history of the bestseller at Temple University. (via Laura B. McGrath)

Publishers lobby hard to get their books in front of the editors who curate that list. Booksellers, who want to move copies, also push for titles they think will be promising.

From there, sales of those books at a secretive list of shops across the country — tens of thousands of stores, according to the company — are examined by three Times staffers.

And that data is what makes up the list, which has run every week in the paper since 1931.

“Sometimes before a book has even sold a copy, it’s deemed a bestseller, just by virtue of the expectations that are placed on it,” McGrath says.

Those expectations have, for decades, favored white authors — so heavily that Essence magazine created its own parallel bestseller lists that drew data from only Black-owned bookstores to reflect what Black Americans were reading.

That favoritism extends to every aspect of creating such a curated list, McGrath says. Publishers bring their own biases to the list of titles they project will do well.

“If you’re completely disconnected from the Black reading community, it’s very unlikely you’re going to say, ‘I have this book by this Black author no one’s ever heard of,’” McGrath says. “And if you do, it’s only if that book by a Black author you think could do really well with the white reading community, which is what publishers are still basing their decisions on.”

The calculation method for the NYT bestsellers list turns up a different list than the USA Today list. (The Hustle)

Beyond that, because the stores the Times includes are a secret, there’s no way to know how many Black- or Latinx-owned bookstores are represented or to gauge the geographic diversity of stores. Historically, the Times used sales in New York as an index for what the country was reading. It has since broadened its reach. (When asked for comment, a Times spokesperson provided this link to its methodology.)

A star is born

The list has been one of publishing’s most powerful marketing tools for generations.

In 1940, writer Richard Wright learned he would be the first Black author chosen for the prestigious — and widespread — Book-of-the-Month selection. (Think Oprah’s Book Club, as a subscription service.) The selection committee had just one condition: that he soften the language and remove one scene they thought might be offensive to their mostly white readership.

Wright knew what the selection would mean for him and his career. He agreed to the changes. His novel, Native Son, went on to sell 215k copies in its first three weeks. He became the first Black bestselling author in US history.

Since then, the list has catapulted unknown authors like Delia Owens, Colleen Hoover, and Bonnie Garmus into new stratospheres of literary and financial success.

Author Richard Wright, the first Black bestselling author in US history, leans over a bridge in Venice in 1950. (Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche/Getty Images)

Even a week on the list can have an impact — provided an author has already earned out their advance. At an average list price of $27.99 for a hardcover, and 5k copies sold, that’s a gross $140k. Authors make anywhere from 5%-15% royalties, which means that’s a tidy $21k week.

“If anything, what appearing on the list does is not so much cause your sales to increase from one week to the next, but rather to decrease at a slower rate,” writes Alan Sorenson, a Stanford University business professor. Insert money-flying-away emoji here.

Still, it’s undeniably something between marketing tool and self-fulfilling prophecy, and remains one of the most coveted accolades in publishing. So, of course, over time, writers have tried to shortcut their way onto it.

The dagger system

To have a shot at a bestseller, 5k copies in a week is generally considered the threshold to clear; 10k if you want to be safe. And if you’re a political figure, say (looking at you, Donald Trump), who already has some money in the bank, buying your way onto it isn’t outside the realm of possibility.

There’s now an emoji for that: A dagger appears next to titles on the list suspected of rising thanks to the bulk-order cheat. And it has signaled nefarious business in a few high-profile cases:

- When Trump’s The Art of the Deal came out in 1991, he instructed staffers to place orders in the thousands to sell at his own properties. In 2016, he used the same strategy with Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again, buying $55k worth of copies himself to ensure the book’s relevance.

- In 2015, Mitt Romney put a twist on the bulk-order bilk: He took at least half of his hefty $50k speaking fee in book sales instead of cash.

- NSYNC superstar JC Chasez’s cousin, Lani Sarem, drew ire for placing bulk orders at shops across the country for her debut, Handbook for Mortals, only after confirming the shops would be reporting their data to the NYT.

The Hustle

Sarem, it turned out, had hired ResultSource, a shadowy San Diego-based consultancy that mounts bestseller campaigns by orchestrating bulk book orders but making them look organic.

After involvement in several scandals of its own, ResultSource’s website went dark. The company also didn’t respond to The Hustle’s requests for comment.

But an older version of its website lists many bestseller campaigns it’s executed for authors, including on Delivering Happiness, Payback Time, The One-Minute Entrepreneur, and If You’re Not First, You’re Last.

According to Forbes, hiring ResultSource costs upwards of $20k, roughly the same amount an author would make from selling the requisite number of copies to land on the NYT list, and a premium if you want to buy your way to No. 1.

Gaming the list

While the dagger connotes malfeasance, there are more aboveboard ways to strategize one’s way onto the list. A team of data scientists at Northeastern University crunched the numbers (nearly 4.5k of them) and traced patterns in eight years of NYT bestsellers, publishing their findings in the journal EPJ Data Science.

The study reveals:

- Some months you have better chances — in February, selling ~3k copies will land you on the list, compared to December’s ~10k threshold thanks to holiday shoppers

- When it comes to nonfiction, memoirs and biographies have the best shot (though it obviously helps if you’re already famous)

- In fiction, suspense novels and thrillers are most likely to make it

- If you’re a woman, you’re more likely to crack the fiction list, and if you’re a first-time author, your chances are best in nonfiction rather than fiction, where repeat authors like James Patterson (260 bestsellers and counting) dominate

The Hustle

In March, Patterson accused the Times of gaming their own list in an open letter excoriating the paper for what he called “cooking the books.”

His new book came in at No. 6 on the list that week, but when Patterson compared the Times’s list to the raw BookScan data — considered the most reliable source tracking all book sales across the country — he saw his name at No. 4.

“Maybe I’m foolish for thinking ‘best seller’ is supposed to be a measure of what’s most popular with my fellow book-buying readers, as opposed to some Times-decreed value judgment on the method by which the books were sold,” he wrote. “At any rate, I’m asking you to please cut it out.”

‘I need to lie down’

In 2020, University of Pennsylvania student Chloe Gong wrote a tweet. “My heart is going so fast I can’t even type!! THESE VIOLENT DELIGHTS is a New York Times Best Seller!!! THANK YOU FOR READING AND PICKING UP THIS BOOK I NEED TO LIE DOWN.”

She’d just become one of the youngest New York Times bestselling authors in history. She wrote her book, These Violent Delights, on summer break after her first year of college, during late nights alone in her tiny apartment.

For Gong, like many authors, the book’s success had a compounding effect. Her next book was promoted with trailers played on screens in Times Square leading up to its release. For another, her publisher commissioned a mural of the cover on a building in New York.

Chloe Gong has landed on two New York Times bestseller lists. (Jeremy Chan Photography/Getty Images)

And when Our Violent Ends, the sequel to Delights, debuted at No. 1 on the NYT young-adult bestseller list, Gong celebrated on TikTok with live recordings of her giggling as her editor delivered the news.

She posted self-effacing videos joking, “the size of my ego when distant relatives brag about their kids going to Ivy League schools and my grandma pulls the ‘my granddaughter graduated from an Ivy League as a New York Times bestseller’ card.”

McGrath, the English professor, points out that the list is as much a cultural signifier as it is an accurate index of what the public is reading. The tagline makes it easier for readers to find a book within today’s info glut and makes it easier for an author to convince a publisher to let them write another one.

“It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy,” she says. “It has a cumulative, rich-get-richer effect, if you’ve managed it successfully.” Sales come and go, but a NYT bestseller bio line is forever.