Allison Severance cradled an apple in her hand. It looked like a deflated balloon — soft, brown and leaking. This can’t be what passes for groceries, she thought. Not on my watch.

She was standing in a Dollar General store a few miles from Cascade, Maryland, where she and a dozen other residents are suing a developer to stop a Dollar General from going up.

“The apples were rotten, the zucchini was rotten, the spinach was slimy,” says Severance, who works as a potter and a ceramics teacher out of a 19th-century barn on her property. “It was horrible.”

Cascade, a village of 840 people, has three dollar stores within five miles of town. When Severance heard her next-door neighbor was selling his land to put up another one she made yard signs for other Cascadians to plant on their lawns. She walked up and down the highway waving an enormous banner that read “Say no to Dollar General.”

Along with a dozen others, she hired a lawyer to fight the developer in court. The village quickly racked up thousands in legal fees; Severance held ceramics fundraisers, donating all of the proceeds to pay for the legal bills.

Allison Severance hung a “say no to Dollar General” banner on the side of her Maryland barn. It’s been there for nearly two years. (Provided by Allison Severance)

“I just can’t believe this has been going on for almost two years,” she says. “Dollar General is invasive. I just pray that the judge says, ‘Enough is enough.’”

Dollar store backlash is happening all over the country. The stores are routinely blamed for gouging consumers, making it harder for stores selling healthier food to open nearby, and failing hundreds of government safety inspections, making the stores so unsafe even shareholders are concerned.

To fight back, like Severance, some ~60 communities have attempted to restrict their growth by limiting their locations or banning them outright.

“I haven’t seen a backlash like this before,” says Kennedy Smith, senior researcher for the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “And I think the reason is, the issue is a perfect embodiment of what the problem is with corporate power.”

But as popular as it’s been to ban dollar stores, replacing them with a viable alternative is much more complicated.

Love ’em, hate ’em, need ’em

In the United States these days, it’s almost impossible to avoid dollar stores.

- An estimated 249m Americans now live within five miles of one, making them nearly as common as McDonald’s franchises.

- A total of 35k stores are owned by Dollar General and Dollar Tree, the two largest players in the space.

- Dollar stores are the fastest-growing food retailers in the US, both by sheer number and food spending.

In 2022, Dollar General raked in $37.8B in revenue, followed closely by Dollar Tree at $28.3B. The stores are also known for serving low-income communities and food deserts, but data cruncher Morning Consult found last year that 45% of households making $100k+ were open to shopping at discount stores, up from 39% the year before.

Basically, people need them. That doesn’t stop people from hating them, too.

The stores offer lower prices while also offering lower quantities, making their wares more affordable, but only in the short term. (More on that here.)

And those wares are notoriously unhealthy. Grocery stores often lose money on fresh produce and make up for it with boxed goods in the aisles — higher markup, lower turnover. Dollar stores take this one step further: They sell only those profitable foods, which are shelf-stable, higher in calories, and lower in nutrients. Most don’t sell fresh produce at all.

Dollar General is planning to change that — the company sells fruits and vegetables in ~3.9k stores, and plans to increase that to ~10k over the next few years.

In a statement, Dollar Tree touted its convenience, ability to create jobs, and potential for economic development. “We often repurpose previously vacant retail space in neighborhoods that have retail needs, keeping centers and other adjacent businesses open and serving communities, especially those that are underserved,” a spokesperson told The Hustle.

Two years ago, an unchecked rat problem in a Dollar Tree warehouse in Arkansas led to an infestation in stores across six states. The FDA issued product recalls that led to 404 stores pulling most of their food from shelves due to live rodents, dead rodents, excrement, and more contaminants.

A shopper weighs his options at a Dollar General in Chicago, where policymakers are considering restrictions on dollar-store development. (Scott Olsen/Getty Images)

The chains’ business model relies on lean staffing, which has made the locations hotbeds for looting, robbery, and other crimes. Last year, at one Ohio store, a customer killed an employee with a machete. According to the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit, dollar stores have been the site of gun violence incidents 727 times over the last nine years. In other words, once every 4.5 days.

Even with stores operating with a single cashier, together the companies employ ~370k nationwide — 0.1% of the entire country works at a dollar store owned by one of the two major chains. (Last year, Bloomberg Businessweek declared Dollar General “the worst retail job in America.”)

For every TikTok influencer showing off their dollar-store grocery haul or sharing their latest #dollarstoredinner, there’s a TikTok calling out the chains for unkempt stores and selling products that are broken, bad, or just plain ugly. “This toothbrush made my baby’s gums bleed,” one mother said.

At @DollarTreeDinners on TikTok, Rebecca Chobat makes a Thanksgiving dinner from scratch for $70 for her 1.2m followers. (TikTok)

Beginning in 2018, municipalities across the country began taking action, and that ripple has become a groundswell. In response to the explosive growth, about 60 communities — including Tulsa, Oklahoma; Kansas City, Missouri; and Mesquite, Texas, among others — have voted to temporarily or permanently restrict dollar stores, using zoning bylaws to do it.

A community in Louisiana recently succeeded in blocking a development in court — a judge decided approving the project would infringe on his residents’ health, safety, and welfare. Cities like Detroit and Chicago are working on their own prohibitions now.

Just one municipality has opted to ban them completely.

One community said no — forever

First to close in Stonecrest, Georgia, was Target. Best Buy followed. Kohl’s pulled out, and then the community lost a Kroger and a Publix grocery store. For a while, the main landmark driving down the interstate into town was a shelled-out hotel, half-finished and abandoned.

In 2018, Walmart closed a Neighborhood Market location and a Sam’s Club in Stonecrest in the same week. Employees arrived at work to locked doors, and left teary-eyed.

Dollar stores were eager to fill the void. By 2019, there were 20 in Stonecrest, Georgia, a city of ~60k mostly Black residents outside Atlanta, giving Stonecrest 3x as many stores per capita as the national average and double the average in the South. “We already had our fair share,” says Mayor Jazzmin Cobble.

That same year, Stonecrest became the first city in the US to ban the stores outright.

Stonecrest Mayor Jazzmin Cobble wants to see a grocery store in each of the city’s five districts. So far, they’re three for five. (Marcus Ingram/Getty Images)

The decision in the middle-class city was wildly uncontroversial. At the city council meeting, even a local pro-development lawyer spoke up only to ensure gas stations wouldn’t be included. (He was representing one at the time.)

“You’ve seen your last dollar store in Stonecrest,” declared then-Mayor Jason Lary. (Lary was later investigated by the FBI for embezzlement of the city’s covid relief funds and arrested.)

The Hustle

But stamping out dollar-store growth doesn’t mean grocery stores sprout in their place. Grocery stores don’t just appear in communities — they’re courted.

Christian Green, who runs economic development for Stonecrest, oversees those pitches. “We’ve said, ‘These are the grocery stores we want to attract.’ And then we target them: we identify who the site selectors are in the industry that specifically do work with those businesses,” he says.

A targeted approach means developing a relationship with them, and coming prepared with stats to make their business case: the area’s density, proximity to competition, traffic counts, and median household income.

In 2021, the city delivered a victory, welcoming Lidl, a German discount grocery store. Dozens of customers turned out for the ribbon-cutting; one man toting a grocery store bag was so excited he lined up at 4:30am.

Even without more dollar stores, attracting businesses has been a challenge for Stonecrest. Calls for a Starbucks have been unsuccessful, as have requests for Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods.

Volunteers hand out ~1k food kits to families in Stonecrest at an event to counteract food deserts in 2022. (Paras Griffin/Getty Images)

Two of Stonecrest’s five districts are without a grocery store, which means ~20k residents have to travel miles outside their neighborhoods to access food.

It’s not as simple as a community saying they want something. “Describing that to an everyday citizen who just wants to see a grocery store, that’s not always a positive conversation,” Cobble says.

Meanwhile, a game of corporate chess, in the form of a messy patchwork of legal cases brought on by dollar stores, is playing out across the country.

Backlash to the backlash

The backlash to all this backlash? Litigation.

Last year, residents in Michigan and Nebraska voiced such vocal opposition to the construction of a Dollar General that policymakers rejected the initial plans. Dollar General’s developers sued, and, faced with the prospect of hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees, the communities folded. The stores are now being built.

Has anyone asked the customers who frequent these stores how they feel about banning them?

Yes, it turns out. The first nationwide survey after the pandemic dollar-store boom was conducted by the Center for Science in the Public Interest, which released the results in October. Respondents — 750 lower-income dollar-store shoppers from across the country — didn’t want to see dollar stores banned. Rather, they relied on the chains for basic necessities.

The Hustle

Other interesting findings:

- 82% felt dollar stores improved their community

- 81% wanted to see healthier options — from pantry staples to fruits and vegetables — at their local dollar stores

“We were surprised at the overall positive perception,” says Karen Gardner, senior policy associate for CSPI. “Our statistics don’t support a national ban.”

Smith, who leads research on dollar stores for the Institute of Local Self-Reliance, isn’t convinced. Even if dollar stores can offer healthier food at checkout, they’ll never replace a full-service grocery store, she says. “Not when a locally owned grocery store provides higher-paying jobs, better security, and a better variety of food.”

Kennedy Smith researches the impact of dollar stores for the Institute of Local Self-Reliance. (Provided by Kennedy Smith)

As discussion around the chains grows more heated, Smith now fields ~20 requests a week for more information from communities hoping to challenge discount stores.

Prohibition mission

What does a ban like Stonecrest’s actually change?

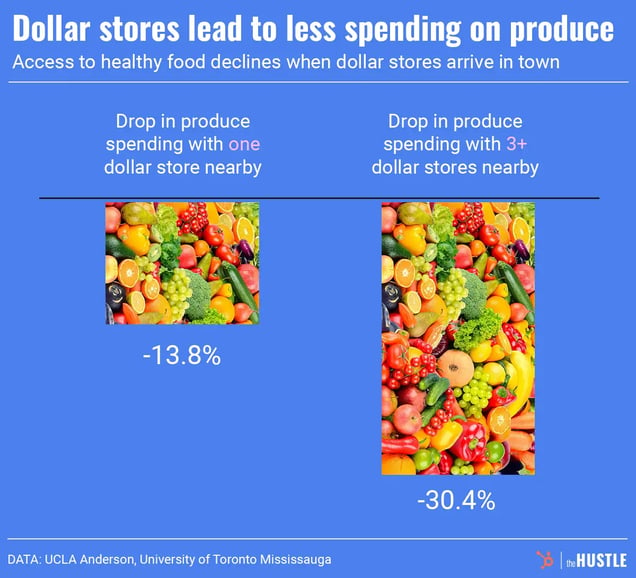

Research from UCLA Anderson and the University of Toronto Mississauga found that one grocery store closes for every three new dollar stores that open. A new dollar store in the market means shoppers buy less fresh produce, particularly if they’re older, lower-income, belong to a minority group, or lack access to a car.

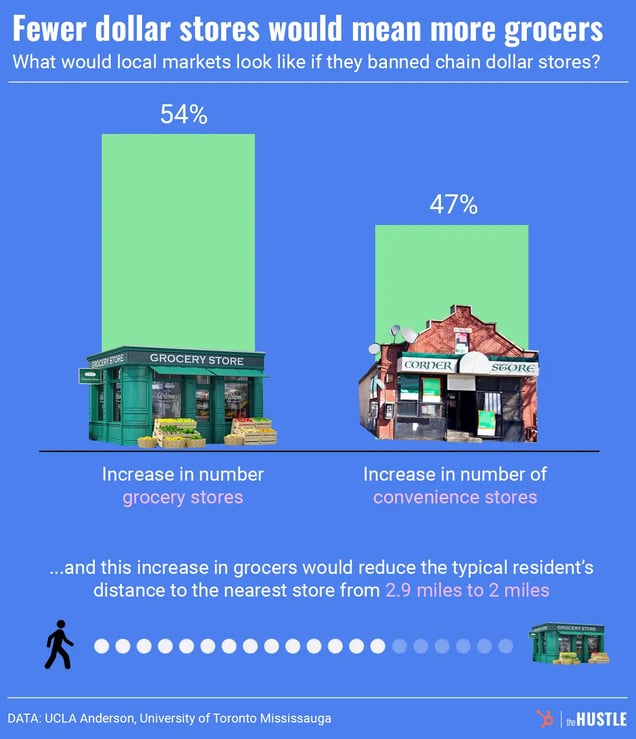

The researchers also gamed out what markets would look like if the influx of dollar stores hadn’t happened at all beyond 2010, and found that the number of grocery stores in the communities they studied would have increased by 54%.

The Hustle

Can Stonecrest’s success be replicated?

Every city needs to decide for itself, Cobble says. “For Stonecrest, it’s been helpful.”

A Dollar Tree in Los Angeles, California. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Perhaps the restrictions’ greatest benefit has been creating space for imagination to thrive.

In dollar stores’ absence, mobile grocery stores now drive across the rural South in RVs, and other operators like Neighborhood Grocery in Detroit and Farmacy Market in Webb, Mississippi, have bought farms to create their own supply chain and bypass chains’ aggressive purchasing tactics. Other communities, like North Tulsa, have eased regulations on urban gardening to encourage selling fresh produce.

There’s no one-formula-fits-all — at least not without federal action, Smith says.

“It’s a stopgap,” she says. “It’s a starting action to buy time to take a broader look at how people shape the kind of community they want."