Inside an old brick building in the leafy town of Haverhill, Massachusetts, you’ll find one of the last vestiges of a once-formidable industry.

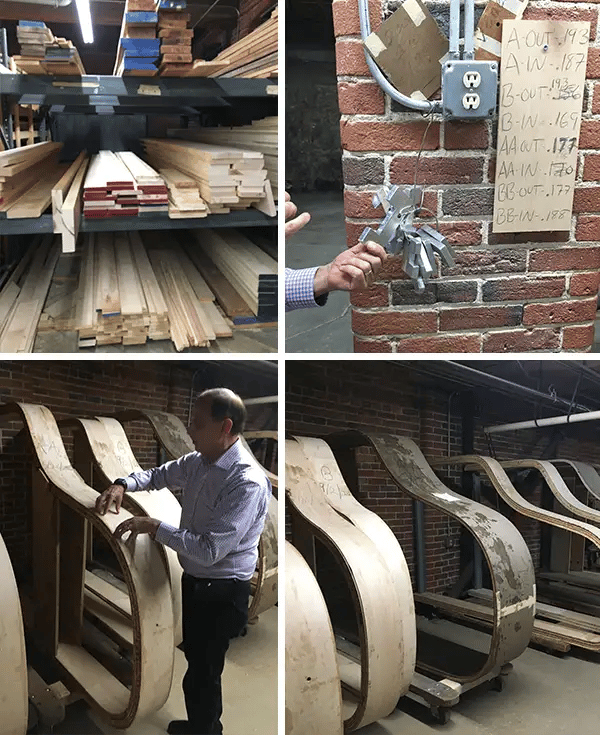

Entering the six-story structure is like going back in time: Stacks of kiln-dried maple wood line the walls. Artisans carefully tinker with tuning pins and soundboards. A light tinkling of classical music rises above the whir and putter of 100-year-old machines.

Not long ago, piano factories like this were one of America’s largest and most formidable industries, employing tens of thousands of workers.

Today, only two active manufacturers remain: Steinway & Sons in New York, and this place — Mason & Hamlin.

Mason & Hamlin’s six-story piano manufacturing facility in Haverhill, Massachusetts (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Over the past century, nearly all American piano manufacturers have been eradicated by foreign competition, declining domestic craftsmanship, and the rise of competing technologies.

But Mason & Hamlin has survived largely by turning to the past, drawing inspiration from a bygone era of artisanry.

The golden age of the piano

Until the late 1700s, the majority of pianos were built in Europe, first in Vienna, and later in Great Britain.

But by the turn of the 18th century, pianos had made their way to the US — and soon, a burgeoning manufacturing industry emerged in industrial hubs like New York and Boston.

William Hettrick, a professor of music at Hofstra University, told The Hustle that hundreds of piano makers popped up throughout the mid- to late-1800s. Chief among them:

- Chickering & Sons (1823) established itself as one of the country’s largest producers, putting out 2k+ pianos per year.

- Steinway (1853) became such a prominent business in New York that it had its own company town within the city that included a foundry, a sawmill, a kindergarten, and its own fire department.

- Joseph P. Hale (often called “the father of the commercial piano”) used an assembly-line process that churned out thousands of pianos at a cheaper price point.

This production was coupled with aggressive marketing campaigns.

“Piano ads were everywhere,” wrote one historian. “It was widely believed that spending money on a piano wasn’t really spending. The money you paid would be embedded right there in this beautiful and useful item. So people would make great sacrifices for these instruments.”

The piano quickly became a must-have in American households — so much so, that in 1867, the historian James Parton declared that “the piano was only less important to the American home than the kitchen stove.”

Early ads touted the piano as an investment in refinement and taste (various newspapers, c.1800s)

Mason & Hamlin was relatively late to the piano party.

Launched in 1854 by Henry Mason (the son of a hymn composer) and Emmons Hamlin (a mechanic and inventor), the company produced pump organs for many years before switching to pianos in the 1880s.

But the market was still ripe for growth, and the company was soon selling up to 500 pianos per year to composers and prominent families throughout Massachusetts.

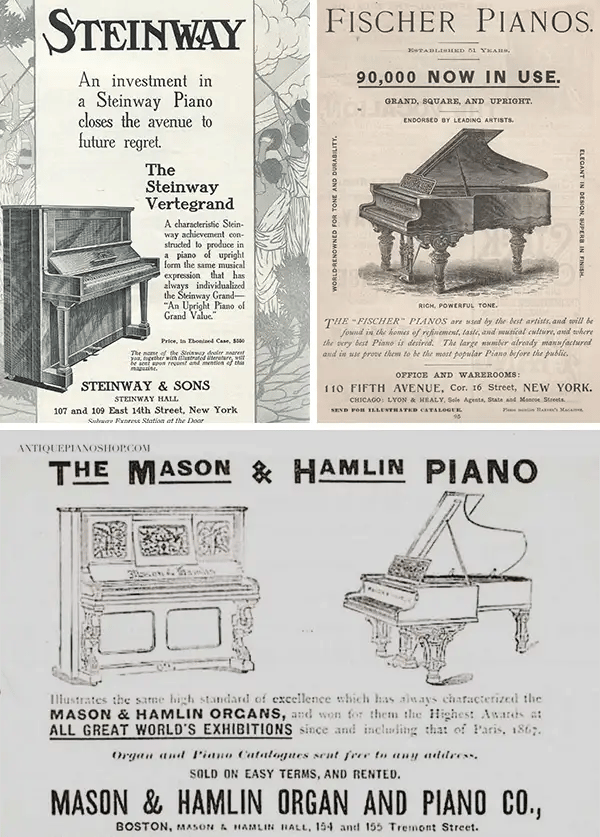

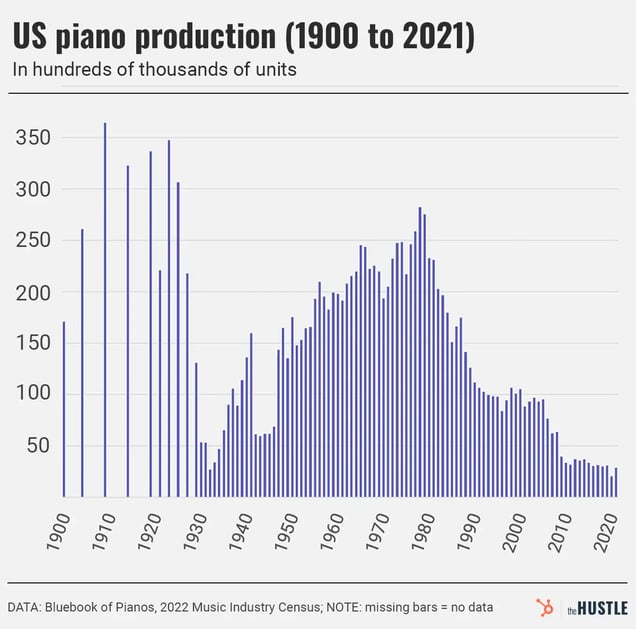

Between 1869 and 1905, the number of pianos produced in America swelled from 25k to 261k units per year. Piano manufacturing became one of the largest industries in the US, responsible for more than 50% of global production.

Then, things came to a grinding halt.

The bust

In the 1920s, a confluence of factors dragged piano sales down:

- The commercialization of automobiles opened up new avenues for entertainment outside of the home.

- The commercialization of radio created a competing source of entertainment inside the home.

- The stock market crash of 1929 tanked disposable income.

During the ensuing Great Depression, piano sales virtually fell off a cliff. Between 1929 and 1931:

- The number of pianos sold fell from 350k+ to less than 60k units per year

- Total US piano sales declined from $42m to $15m

- 85% of piano workers were laid off

The state of affairs only worsened when, during World War II rationing, many piano factories had to pivot to producing military gliders and coffins.

US piano production declined precipitously following the 1929 stock crash (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Mason & Hamlin, which was known for its high quality and attention to detail, soon fell on hard times.

The company changed hands numerous times before getting snatched up in 1929 by Aeolian, a competitor, for $450k (~$7.7m in today’s money). A few years later, Aeolian merged with American Piano Company and moved operations from Massachusetts to Rochester, New York.

Under new leadership, and in a new era of capitalism, Mason & Hamlin’s craftsmanship slowly deteriorated.

“They started making a lot of economic concessions,” Tom Lagomarsino, Mason & Hamlin’s current EVP, told The Hustle. “They switched from maple to mahogany, then to poplar wood. The quality took a big hit.”

The beginning stages of Mason & Hamlin’s piano construction at the company’s factory in Haverhill, Massachusetts: Wood is selected, shaped into rims, and dried out for up to 30 days (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

In the 1960s, the once-formidable US piano industry hit more snags:

- The TV took over as the definitive entertainment source in American households.

- Record players and a cultural shift toward rock music chipped away at the appeal of pianos and classical music.

- Foreign competition began to creep into the US piano market.

Japanese manufacturers, who had been building their own pianos since 1900 with lower labor costs, sensed an opportunity to enter the US market at a lower price point.

In the early 1960s, Japan’s largest manufacturer, Yamaha, established a foothold in the US and began distributing pianos to American consumers. Within a decade, foreign builders from Japan, Korea, and China had more than doubled the sales volume of US manufacturers.

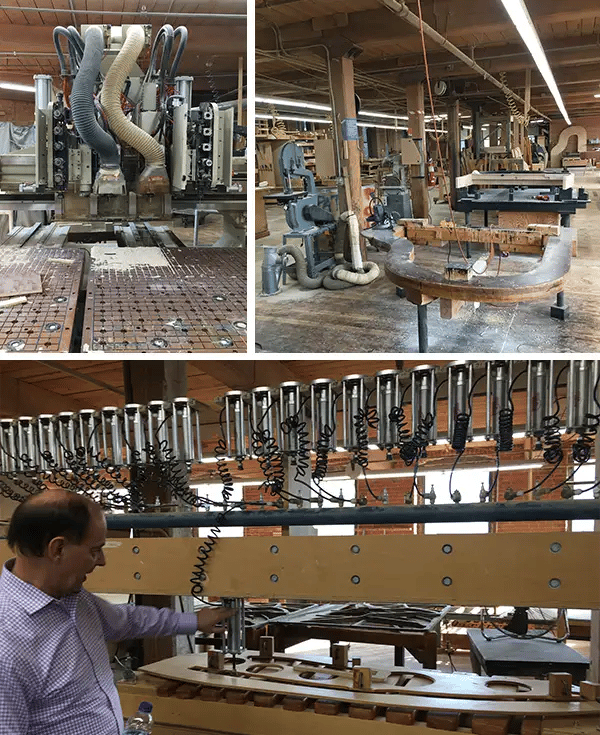

Parts of the piano-building process at the Mason & Hamlin factory (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

American piano builders all but disappeared: By the mid-1990s, only nine remained in business.

A once-bustling US industry was largely dead.

A comeback

In 1996, an entrepreneur named Kirk Burgett saw an opportunity to revive one of the US’s last piano manufacturers.

A decade earlier, Burgett and his brother had invented PianoDisc, a device that enables a piano to play itself for guests. The company grew rapidly and sold 120k units to customers including Nancy Pelosi, Bill Gates, and pro sports stars.

Burgett caught wind that Mason & Hamlin, one of the preeminent piano manufacturers of the golden age, was up for purchase in bankruptcy court.

“We just decided to take a risk and save it,” Burgett told The Hustle during a recent visit to the company’s Haverhill factory.

When Burgett bought Mason & Hamlin, it was a “husk.”

“The creditors gutted the building of inventory,” says Burgett. “We didn’t get a single piano out of it.”

Pianos begin to come together after a months-long process at the Mason & Hamlin factory (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

Burgett realized that the greatest pianos were those built during the golden age in the early 1900s.

So, he slowly started to rebuild — by turning to the past.

- He hired a team of three engineers to digitally reconstruct blueprints of the high-quality pianos the company gained a reputation for in the early 1900s.

- He turned back to many of the original innovations and materials the company had used a century earlier.

- He spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on specialized tools, many of which were decades old.

- He equipped each piano with a tension resonator, a device pioneered by Richard Gertz, a Mason & Hamlin engineer, in 1895.

Unlike other business builders, who push things out before they’re ready, Burgett invested in quality over quantity.

It took him and his team an entire year to produce the first piano, and the company’s first employees went through a two-year training process to build a product up to the standards of 19th- and 20th-century craftsmanship.

And then there were two

Today, Mason & Hamlin is one of just two remaining piano manufacturers in the US that are currently active. The other is Steinway.

While Steinway enjoys a more prominent brand and a larger market share, Mason & Hamlin is boutique, producing around 2.5 pianos per week.

Though the production process is now more efficient, it still takes the company up to 9 months to build a concert grand piano, which retails for $175k.

“There’s really no shortcut to the process,” says Lagomarsino, Mason & Hamlin’s EVP.

Kirk Burgett stands with one of his Mason & Hamlin pianos (Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

In the factory, the complexity of this process — which spans six floors and requires the labor of dozens of workers — is on full display. One piano requires anywhere from 150 to 400+ hours to complete.

Among the steps:

- Hardrock maple is carefully selected to withstand humid summers and frigid winters without warping.

- Rims, which form the shape of the piano, are cut, bent, and stored in a heated room for up to 30 days.

- Bracing structures are fitted in place, along with a tension resonator, which prevents the wood from contracting.

- A spruce soundboard is cut and fitted with ribs

- Hundreds of notches are hand-cut in the bridge

- Polyester paint is applied

- A maple pin block is drilled and hundreds of wires are manually installed, along with tuning pins

- The piano is tuned and tested with up to 40m keystrokes

Burgett says that despite the setbacks the piano industry has faced over the years, business is good.

The company is back-ordered for six months, with robust demand from schools, churches, musicians, and wealthy professionals. During covid, interest in pianos increased significantly, with acoustic piano sales seeing a 46% boost in sales volume in the 2020 fiscal year.

“People were stuck at home and had money to buy pianos,” says Lagomarsino. “There was also a shortage of foreign pianos due to astronomical freight costs and delays. Docks were closed. So there was a revitalized demand on the homefront.”

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Globally, sales of acoustic pianos in 2021 amounted to $403m. Of 29.2k units sold, only around 3k (~10%) were produced in the US.

But Mason & Hamlin’s main challenge as a business isn’t globalized production; it’s the fight to keep a 300-year-old product relevant as new technologies — video games, computers, the internet, cellphones — eat up an increasing share of consumers’ leisure time.

“Our competition isn’t other piano manufacturers,” says Burgett. “It’s other forms of entertainment. People spend $250k on home audio systems, but they still won’t buy a piano.”

Burgett doesn’t think piano sales will ever return to golden age levels. But he knows his business still has more notes to hit.

“People thank us for keeping the company alive and bringing back these pianos,” says Burgett. “The legacy of these instruments is just too strong to die.”