This story is adapted from Kingdom Quarterback (Dutton, 2023), a book that explores how American cities grew and failed, how they are changing, and how football came to mean so much to them, told through the lens of Kansas City and Patrick Mahomes.

On a chilly February day earlier this year, downtown Kansas City exploded in celebration because of football.

Residents started filling the streets at 6am. Children, given the day off by local school districts, tossed footballs near a popular entertainment district, where bleary-eyed 20-somethings formed a line outside the bars. Vendors hustled around Grand Avenue selling unlicensed T-shirts and bottles of water.

A few hours later, with close to 1m people on hand, a caravan of double-decker buses rolled through downtown, officially starting the Super Bowl parade. The man who made this all possible, superstar quarterback Patrick Mahomes, stood on the top level of one bus, hoisting his MVP trophy with one hand and a Coors Light with the other.

Fans couldn’t get enough, cheering wildly when Mahomes showed off a golden championship belt around his waist and when he chugged his beer and spiked the can in the street. They even applauded when he exited a port-a-potty.

The rapturous embrace was emblematic of Mahomes’ hold on the city.

“He’s really raised everybody’s level of joy, right?” Clark Hunt, co-owner of the Chiefs, said during a media scrum before the Super Bowl. “He is the single-most important person in Kansas City right now, and you can argue that maybe it shouldn’t be a sports figure. But it is.”

The same could be said for Giannis Antetokounmpo in Milwaukee and for LeBron James when he played in Cleveland. The superstar athletes have brought championships and excitement to everyone in their region. They’ve given millions of people around the world a reason to pay attention to cities that they never would otherwise.

It’s even possible that superstars like Mahomes have improved some fans’ finances. Local tourism organizations claim millions in benefits from major sporting events. Super Bowl victories in the ’90s were found to increase the per-capita income of residents of the cities that won the big game by $140 (a 1% gain relative to the mean salary and ~$240 today).

Do transcendent athletes really pad the coffers of local businesses and create jobs? How good for the economy are they?

The athletic equivalent of a Fortune 500 company

In the early 1990s, Chicago leaders faced a crisis: What was the city going to do without Michael Jordan?

After consecutive championships in 1991, 1992, and 1993, the NBA star announced his retirement following the murder of his father. Amid the Chicago Tribune’s coverage was a surprising headline: “Area’s economy could take a hit without Jordan.”

In 1993, Michael Jordan shocked Chicago by announcing his retirement from the Bulls. (Getty Images/Ralf-Finn Hestoft)

Jordan, a superstar with unprecedented media appeal, made fortunes for the companies he endorsed. (Example: The Illinois lottery said Jordan’s presence in ad led to an 8x return on investment.) But John Skorburg, chief economist for the Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce, ran a calculation in 1993 and claimed he was a civic asset, too, bringing $1B in value to the Chicago area.

“If Michael Jordan were a corporation, he would be in the Fortune 500,” Skorburg said at the time. “He is the $1B man.”

Part of Jordan’s economic impact was obvious: bringing in more taxes. Since the 1970s, economists have connected attendance bumps to superstars (the Bulls’ per-game attendance tripled under Jordan in the ’80s), and a cut of tickets and concessions filters to local governments.

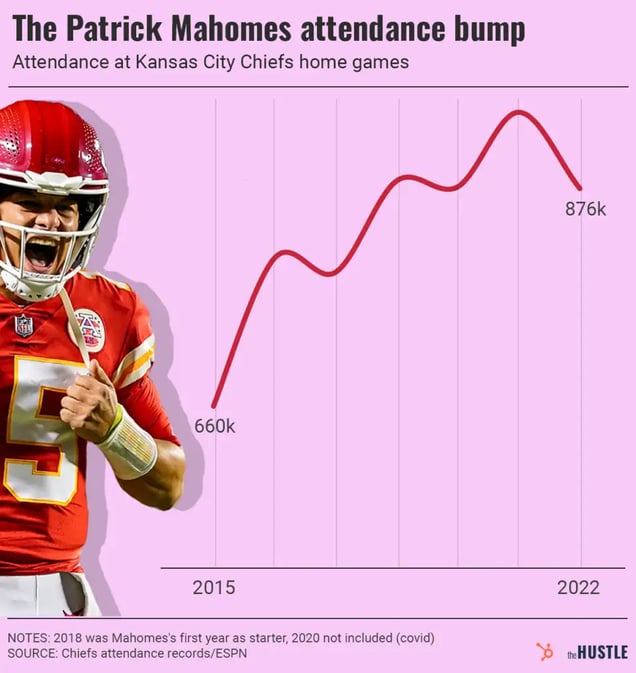

Even in the NFL, which has fewer games and more consistent attendance than other leagues, the presence of Mahomes has correlated with more home games, more fans, and higher ticket prices in Kansas City:

- In 2012, when the Chiefs tied their franchise record for losses, the TMR Fan Cost Index at Kansas City games (the price of four tickets, four sodas, two beers, two souvenirs, and a parking spot) was $360.68. It went up to $430.94 by 2018, the first year Mahomes started at quarterback, and last year rose to $587.47.

- Average annual home attendance has increased from ~751k per year in the four seasons before Mahomes became the Chiefs’ full-time starter, to ~897k in the four seasons since (excluding the covid year of 2020), due, in large part, to the team hosting at least two playoff games per season. The team had hosted just four playoff games in the prior 20 years.

Kansas City, its county, and the state of Missouri take ~9% sales tax on tickets and concessions. Based on 2022 attendance of 876k and using estimates from the Fan Cost Index, taxes totaled ~$11.6m last year. That’s up from ~$8.6m in Mahomes’s first year as a starter and ~$5.5m in 2012.

The Hustle

But superstar athletes may generate more than taxes. Skorburg attributed $150m in tourism to Jordan, tens of millions in TV and ad revenues for local media companies, and a major chunk of change for local merchandise sellers.

The millennial Jordan, LeBron James, brought similar benefits to Cleveland off the court. When he played in the 2010s, Cleveland moved into the top 30 as a convention destination, and economists Stan Veuger and Daniel Shoag traced a rise in bars and restaurants that shadowed James’ return to the city in 2014 after leaving for Miami.

- Within one mile of Cleveland’s and Miami’s arenas, the number of eating and drinking establishments increased by 13.7% because of James’ presence. The number of people employed by eating and drinking establishments went up by 23.5%.

- The effect was hyperlocal, dissipating outside of seven miles from the arena.

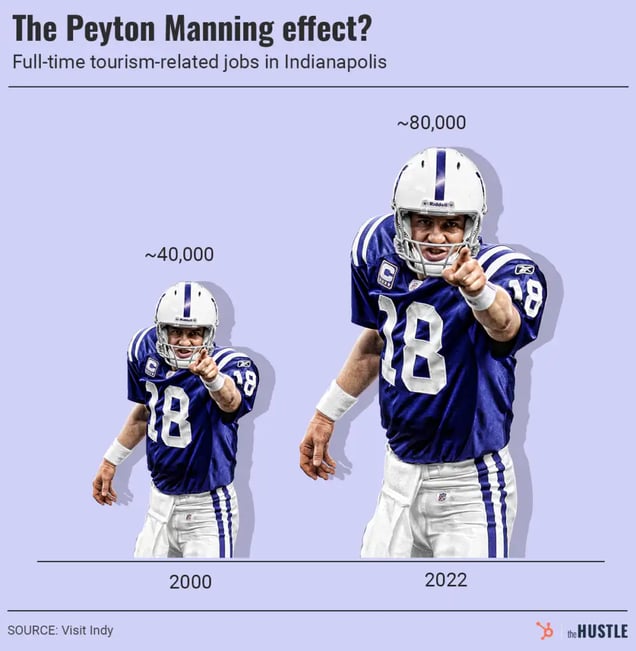

Perhaps no modern athlete has been credited with reviving their home city like Peyton Manning for Indianapolis. On the field, the Colts went from a bottom feeder to a champion, and the city saw its number of annual tourists rise from 16m in 2000 to 30m in 2022, coinciding with dozens of national TV appearances that the tourism agency Visit Indy suggests were worth $700m in free advertising.

Manning was an active participant in the city’s newfound popularity. He visited the statehouse to lobby for a new stadium, which has been used for numerous conventions, the 2012 Super Bowl, and annual Big Ten football championship games. According to Chris Gahl, executive vice president of Visit Indy, Manning also helped the city convince at least six conventions to come to Indianapolis by meeting with organizers during their bid process.

Compared to James, Jordan, and Manning, the Mahomes era in Kansas City is in its early stages. But by leading Kansas City deep into the postseason every year, Mahomes has opened up new opportunities for revenue.

- During conference championship playoff games hosted by the Chiefs for the last five years, leaders have claimed the city experiences $13m in economic impact. Hotels, according to local news station KCUR, have seen occupancies at 80%, up ~30 percentage points compared to normal January weekends.

- The Super Bowl berths have been a boon for many restaurants. At Joe’s Kansas City BBQ, a famed eatery, VP of operations Ryan Barrows said the restaurant received more than double the number of sales they’d expect in the two weeks leading up to the 2020 big game, comparable to what they’d see at Christmas or Thanksgiving.

Tailgating at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City. (Getty Images/Icon Sportswire)

Perhaps most noticeable in Kansas City is a vibe shift. As local pastor Ron Lindsay says, people “are finding a different meaning in the city because of this team.”

But in sports economics, as in the games themselves, there are always catches.

The superstar skeptics

Victor Matheson, an economics professor at Holy Cross University, has a rule of thumb for when he hears sports-related economic claims from a chamber of commerce or tourism department: “Move the decimal point one place to the left.”

Matheson is known for studies debunking the economic benefits of stadiums and mega events like the Olympics and the Super Bowl. He acknowledges some benefits of sports and superstar athletes: They precipitate increased tax revenues and more tourists and hotel stays, especially in the NFL and MLB.

“There is more economic activity generated by the Chiefs now than in the past,” Matheson said. “There can definitely be a Mahomes effect, and there’s no question there’s a LeBron James effect as well in terms of the revenues you can clearly see being generated by Mahomes and the Chiefs and the Cavs and LeBron James… But what’s less clear is on a macro level whether that has any effect on Kansas City.”

One of the murkier questions economists ask about sports is whether they bring new spending to the economy or rearrange spending that would occur somewhere else, as a substitute. The gravitational pull of Jordan, for instance, may have led Chicagoans to attend basketball games instead of going to concerts or eating at restaurants. The jobs for Chicagoans at the Bulls’ arena may have existed in other parts of the economy.

LeBron James returned to play for the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2014, benefiting local businesses. (Getty Images/Mike Ehrmann)

The substitution effect is difficult to pin down, Matheson said. And the ways in which sports are a substitute for economic spending vary depending on the market.

- In the study about James, economists Veuger and Shoag saw an increase in bars and restaurants near the basketball arenas in both Cleveland and Miami. But they noted that in Miami, a haven for tourists and partiers, similar economic activity would’ve occurred regardless.

- In Cleveland, however, the new restaurants and bars counted as activity that likely wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

“What I wanted to write in the paper is obviously in Cleveland, there’s nothing to do, so you have a big spillover effect,” Veuger said, joking about Cleveland’s flyover reputation. “Whereas in Miami, you have all sorts of other things to do. And so a super successful basketball player just isn’t as much of an attraction in relative terms.”

Even in places like Cleveland and Kansas City, just because people are spending doesn’t mean the public is reaping the benefits.

While the tax revenues from tickets and concessions flow to the city, it’s unclear whether the bulk of spending associated with sporting events circulates back into the local economy.

- In the hotels that benefit from extra occupancy and higher rates during big games, much of the new revenue goes to the national ownership, “leaking” out of the regional economy.

- At the games, Matheson says money spent on NFL, NBA, or MLB teams typically flows to the billionaire owners and athletes, who usually spend half a year in the cities where they play. Meanwhile, workers for teams often must protest and file labor complaints to receive raises.

Dodgers workers protest before a June 2023 game in Los Angeles. (Getty Images/Media News Group/Pasadena Star-News)

And then there’s the stadium-sized hole out of which many cities must climb.

From 1970 to 2020, public subsidies for US stadiums totaled ~$33B, covering 73% of total costs. Despite claims from elected officials, a 2022 paper by professors John Charles Bradbury, Dennis Coates, and Brad Humphreys that surveyed decades of research showed “near-universal consensus evidence that sports venues do not generate large positive effects on local economies.”

Superstar athletes, of course, don’t need any tax subsidies, but owners have often leveraged the success of a superstar athlete — John Elway in Denver, Manning in Indianapolis, James in Cleveland — to convince the public to pay for renovating an existing stadium or building a new one.

Any amount gained from a superstar effect, according to Coates, an economics professor at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, does not justify the cost of a subsidized stadium.

“Not even remotely,” he said. “We’re talking about the rounding error.”

A zero-sum game for cities

Whether you believe a superstar athlete merely brings increased tax revenues and extra hotel visitors or creates jobs and attracts events worth economic value, it’s easy to see why cities would want them.

- Unlike stadiums, they’re a bargain, bringing exposure while requiring no public investment.

- They give residents something to rally around.

And not unlike athletes, cities are engaged in a zero-sum game, squaring off against other metros for a limited number of conventions and tourists and businesses. Many of their leaders believe any edge can help.

The Hustle

As Gahl, the executive vice president of Visit Indy, recalls, a major convention in the mid-2000s was choosing between Indianapolis and Baltimore. It happened that one of the convention’s organizers was a huge Manning fan.

“Peyton popped over and talked for 10 to 15 minutes about Indianapolis and what he liked about the city,” Gahl said. “Ultimately they picked Indianapolis.”

Indianapolis won, which meant Baltimore lost.

Matheson notes that this type of story reveals the big-picture impact of superstars: In most cases, they’re a wash. The presence of Manning didn’t generate anything for the country as a whole — just a few gains for one region.

Not that the cities lucky enough to have a superstar are complaining.

Kansas City notched its own surprise victory when, in June 2022, FIFA announced it as one of 11 US host cities for the 2026 World Cup. Kansas City was the smallest city selected and chosen over more prominent locations like Washington, DC, and Nashville.

Did the added visibility of Mahomes offer Kansas City an extra edge? Who knows. But when Kansas Citians celebrated the win at a popular downtown entertainment district, a familiar face popped up on a large screen to toast the victory with them: the superstar quarterback himself.